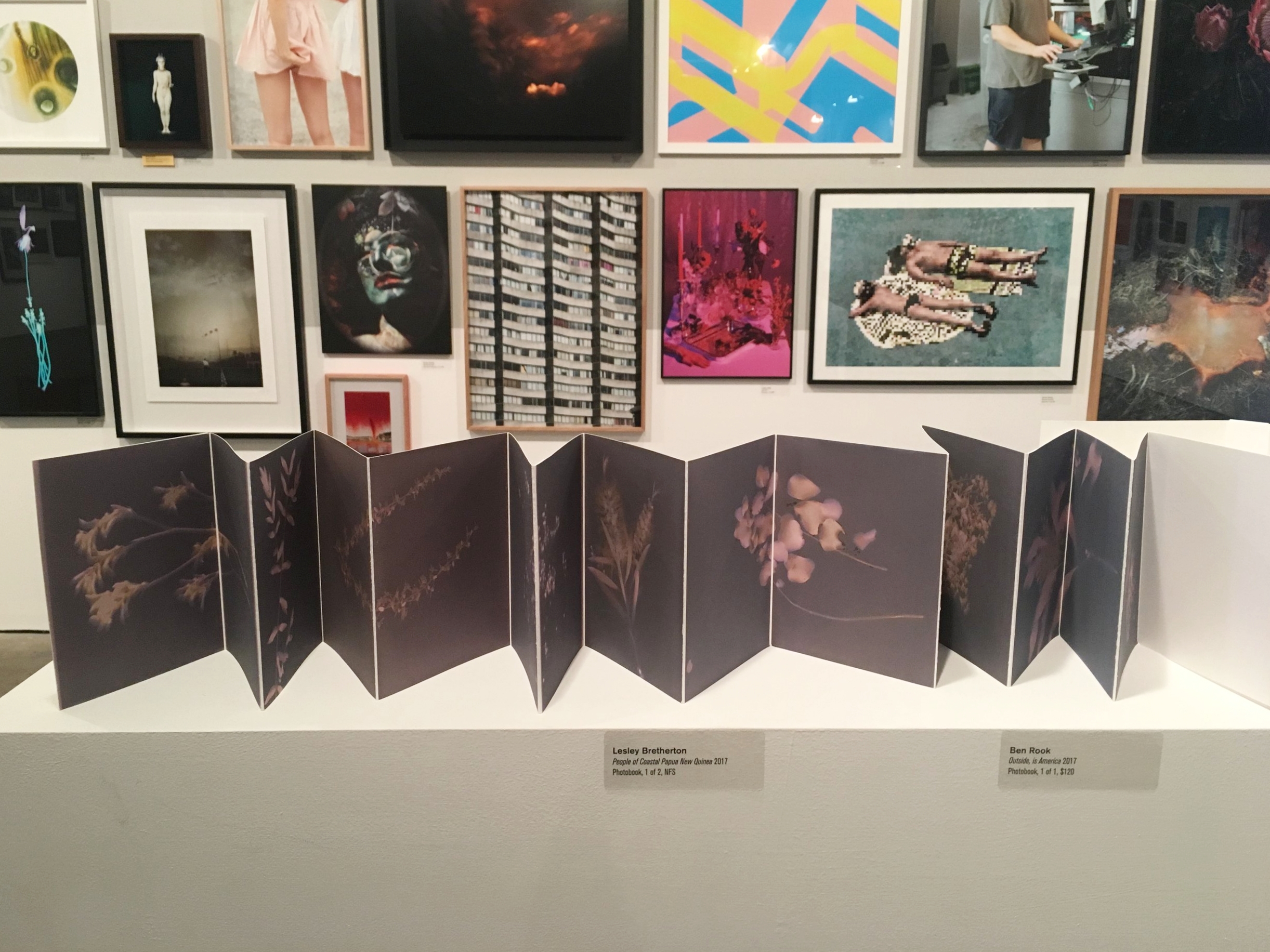

Reading Wesley Stacey’s ‘Signing the land | Segni Sul Paesaggio’ (1993) is a physical experience. As a book that you can literally surround yourself with, if opened fully it might even verge on being called challenging. Created from one long folded sheet of paper, each of the black-and-white landscape scenes is surrounded by an ample white border and includes a caption, in both English and Italian, detailing the ‘signs of life’ that have drawn Stacey’s eye.

Often the images stretch across a fold to fit both the elongated form of the image and the concertina of the book. When folded down they form a double-page spread. Since the 1980s, with his adoption of the WideLux camera, Stacey has employed the panorama to greatest effect when situating the viewer within the landscape. You’re not just looking at it, you’re in it. There is a sensitivity to his work that is influenced by time spent living in his bush camp on NSW’s South Coast (where he still lives today) and working with Aboriginal Elder Guboo Ted Thomas in the late 1970s to document Aboriginal heritage sites.

Signing the land, is a treasure hunt of sorts, in each scene there are the marks of humans upon the landscape. The book combines images from a trip to Italy in 1988 and scenes from Stacey’s travels around Australia – from the shells left on a beach indicating a traditional eating place, to the scratching of a name into a centuries-old column in Italy as a form of remembrance. Some may see these marks as graffiti but Stacey’s images take on a different perspective. The smooth black-and-white tones make these scrawled messages part of the texture of the landscape – another weather-worn aspect of that place, a topographical map of sorts. These marks, signs and graffiti testify to a shared experience between cultures, the need to remind people of future generations that we were here, we existed.